During the past year or so, and especially in the last few weeks, I owe a great deal of thanks to a machine I call a PDF scanner, since I don’t know what it normally called.

The scanner looks like a photocopy machine with a computer screen attached to it. Like a regular photocopy machine you can use the glass or the feeder on top to copy documents and books at the same speed as you might expect from such a machine. However, instead of charging you money and outputting these copies on regular paper, the result of the free scan is displayed as thumbnails on the screen to the right. When you are happy with the resulting scans, you may save them together as a PDF (or as separate image files) and have the file sent to a USB drive or to a server of your choice via FTP.

The machine can be set to a number of resolutions (200 dpi and up) and scans in black and white, grayscale, or color. You may also indicate the paper size of the scanned image. If you are using the feeder tray, you may scan either single or double-sided documents. The model I have used on campus does not have shrink or enlargement features available and lacks some of the other advanced features we are used to dealing with on a regular photocopy machine. However, if you are scanning English language documents, there is one wonderful extra feature: Putting a check next to “Hidden Text Layer” will direct the machine to OCR the scanned pages of text and make the PDF documents searchable. The accuracy is far from perfect, but more than good enough to make those usually dead images great for keyword searching.

This machine, and in one case a different variation of it, can now be found at several library locations throughout the Harvard campus. Competition for its use is heavy in some libraries, especially those where visiting researchers are desperate to copy materials before they return home and want to avoid the costs of large amounts of photocopying and the weight of carrying these copies back.

The advantages of this machine are huge:

1. Use of the machine is completely free (at least on our campus). This has probably saved me hundreds of dollars in the past year and a half or so.

2. Except when scanning poor quality documents or large amounts of double-sided documents using the feeder tray, there are far fewer jams and other problems which arise with using a photocopy machine.

3. There is no wasting of paper or ink. No paper also means no lugging around heavy photocopies.

4. The scans are at a very high speed and surpass the speed of any but the most expensive personal scanners and is much faster than most document feeding trays I have seen.

5. The scanner’s glass is much larger than all but the most expensive personal scanners and can thus easily handle very large books.

6. The OCR text recognition provides no opportunity for correcting mistakes but is transparently built into the scanning process. You never actually see it happen. It adds only a short time to the final saving of the document as it is transferred to the USB drive. This dramatically reduces the time the OCR process would take if you were to do it after scanning documents on a personal scanner with something like OmniPage Pro or using Adobe Acrobat Professional or other tools.

7. Easy OCR means searchable PDFs which means faster research through your own scanned materials.

Potential general complaints from the perspective of librarians and researchers:

1. The product is a scan – which you view on a screen. This is less fun to read than on paper and less convenient to annotate and scribble on.

2. Free and fast copying means that violating copyrights in the library is now free and fast too. Since the products are PDF files, rather than a single hard copy, it is easier than ever to distribute these PDF in ways that violate copyrights.

What have I found this useful for?

1. I digitized the entire Sino-Japanese studies journal, which is now hosted online. I have been wanting to do this project with Josh Fogel for a long time and only with the introduction of these PDF scanners around campus has it become something manageable with a limited budget of time.

2. I have boxes upon boxes of photocopies that I have made throughout the years. Dragging them around is a pain. The PDF scanner has allowed me to eliminated several boxes of paper (I simply haven’t had the time to go through them all, and I want to keep some highlighted materials and materials that don’t scan well). These documents are now all on my computer, and backed up on other media.

3. I often take handouts from presentations, various mail and personal documents, and scan them up quickly using the document feeder.

4. Any books I might need to have as reference in the field but which I don’t want to bring with me in my baggage, I simply scan up before I go. It takes me about 30 minutes to scan a 300 page book, or about ten pages per minute. It takes another 2 minutes to save the book if you choose black and white at 200 dpi. This means that many of my favorite history books in my field are not only on my computer, but those in English are easily searchable, thanks to the OCR feature included on the machine. I can then leave the original book in storage while I travel around in East Asia. When you are sitting in an archive or on a train in the middle of nowhere, without any internet connection or access to Google books and other search engines – there is nothing like being able to search through a lot of locally stored data on one’s own machine.

Wish List for the Future

1. As more and more people around Harvard campus discover the power of these machines to reduce paper and produce OCRed PDF files of everything from our personal papers, I have watched as competition for their use has exploded – especially for the PDF scanner in Harvard-Yenching library. I hope that the librarians come to see that the advantages outweigh the disadvantages and add more machines to the collection. I would also love to see PDF scanners in libraries and especially archives around the world. The National Archives, for example, is perfectly happy to have me click away with my personal camera at thousands and thousands of pages of articles but still charges considerable photocopying fees. If the archives had a PDF scanner (perhaps the alternative kind found in Harvard’s Widener library Philip Reading room which is face-up rather than face-down and thus less damaging to books) they could seriously cut on machine maintenance fees while providing an incredibly valuable service to researchers.

Obviously the question of copyright needs to be addressed – but the solution is not to cripple the gains from technology advances that improve on existing tools that perform the same essential task: the paper-based photocopier, the slower personal scanner, and the camera, all of which we have had for years.

2. I would love to see these machines support OCR in many more languages.

3. It would be nice for there to be some kind of semi-automated “submission” or “registration” system for scanned materials so that eventually you can reduce the physical burden on the scanned materials in libraries and archives. If certain pages, articles, or archival documents have been scanned before, and are found in the system, then you could simply retrieve this previously scanned document and thereby contribute the preservation of the original by not subjecting it further copy.

4. I would like these machines to have more options than the software they currently have provide such as enlarge/shrink options, crop features, auto-crop features, more media size options, much better color scans of glossy photographs, etc.

Honorable Mention

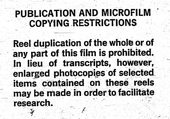

Another similar machine that I also owe a lot to recently is the Microfilm PDF scanner. A number of my recent postings at Frog in a Well and contributions to the Frog in a Well Library refer to documents that I found on microfilms. The documents I have been uploading are PDFs directly created by the PDF scanning software on the computers attached to the microfilm reading machines that I use in the Government Documents section in the basement of Harvard’s Lamont library. It works very much like the microfilm printers we have seen in libraries for years but this time the product is a PDF rather than paper copies. Like the regular PDF scanner above, all these scans are free and allow me to easily share my findings with others.